Personal Works

“Identity in Process”

2016

In late 2015, I found my voice through a new style of painting. The process has become one of the most important elements of my work, reflecting on the identity struggles that I face as a Métis youth. For this work I decided to document my process through video as a way of highlighting the importance of my artistic process, a part of my work that very few people see. The film is my attempt to give my process equal significance to my finished paintings.

Each scene in the film shows each step of my process, and each step reflects a certain aspect of our history as a people within Canada. The mixing of pigments in the beginning of the film reflects on the ethnogenesis and emergence of the Métis people. The blurred focus represents our people losing touch of and rejecting our culture. The peeling of liquid frisket represents the stripping of Métis culture that took place in residential and day schools which aimed to “kill the Indian in the child”. The white paint covering the mixed colours below references the assimilation process which halted the transfer of Indigenous knowledge and pushed us to blend into the dominant culture. The beading in the end of the film represents the reclaiming of our culture after many years of silence and oppressions of our people. The words that I speak at the end of the film are in Michif-French, one dialect of the Métis peoples traditional language. I went to a group of knowledge keepers in our community to learn the phrase, “Chrpren ma keultseur, erprend ma voyoi, erprend kikchu” which means “we are reclaiming our culture, reclaiming our voice, reclaiming our identity”. The words are played over the scene of me beading, further reinforcing the strength and resilience of our people.

"Identity in Process" in my exhibition space at the Ode grad show in 2016.

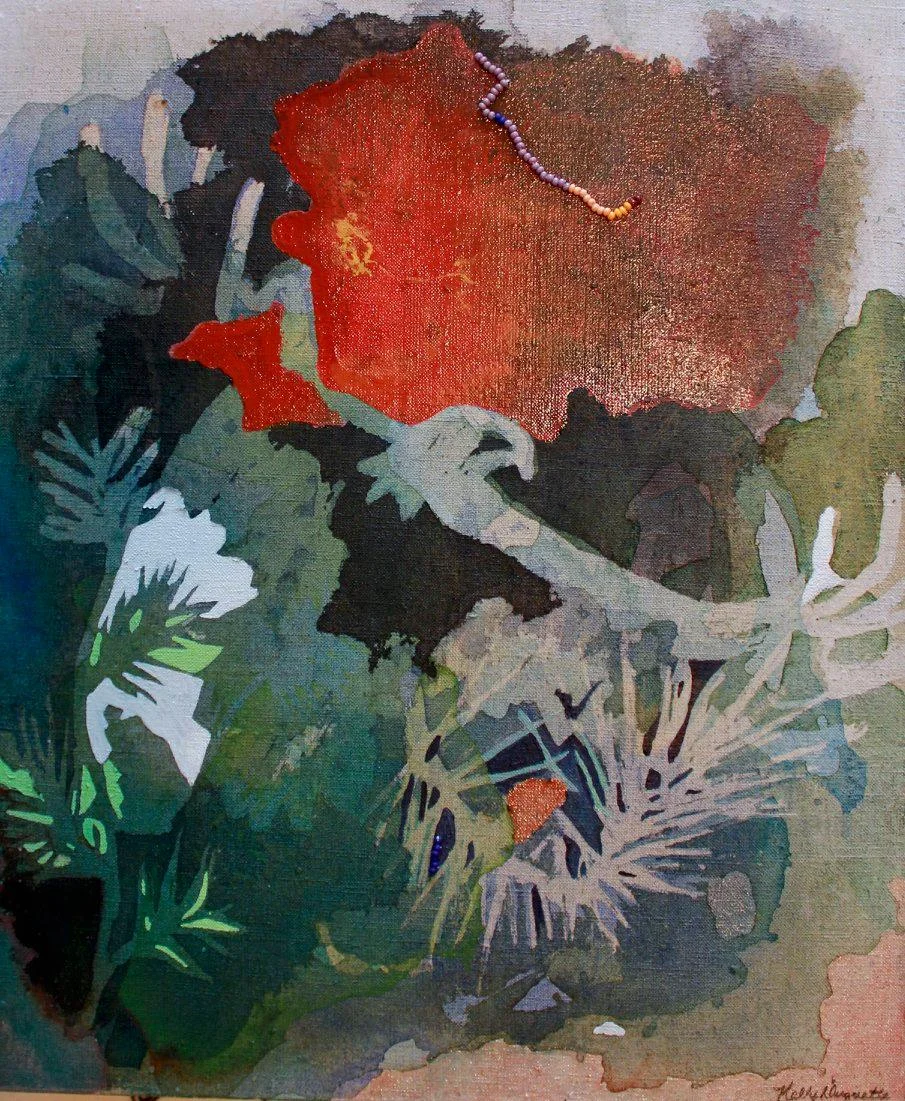

“Lii Chiiraan”

2020

Acrylic paint, dispersion pigments, pouring medium and beadwork on stretched canvas.

Unavailable

12” x 16”

My Shawl

2019

Beadwork through deer hide.

“Te Where Whakapiki Wairua - The House that heals the Spirit”

2019

This painting symbolizes key elements of the New Zealand Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Courts. The adult Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court (AODTC) in Auckland, New Zealand was established as a pilot project in 2012 to address recidivism caused by substance-abuse and the overrepresentation of Maori peoples within the prison system. As an alternative to prison, the two AODTC’s were designed to “break the cycle” of offending by moving away from the adversarial, punitive, criminal justice model to a non-adversarial model that is both therapeutic and restorative in nature. During my placement in Auckland, New Zealand, I worked for Professor Tracey McIntosh at the University of Auckland supporting decarceration and prison reform initiatives. For five of the seven weeks, I observed the pre-court and open-court sessions of the AODTC and attended the treatment facilities to gain a deeper understanding of the participants perspectives as they navigated the court system. At the end of my placement, I drew on my experiences in the development of a final report for my supervisor which outlined my observations in the AODTC. My favourite aspect of the AODTC was that they were designed to reflect the Treaty of Waitangi, where both Maori Lore and Common Law were equally applied within a modified version of the Common Law Courtroom. My placement in New Zealand taught me what true reconciliation looks like and what could be done to address the over-criminalization, over-victimization and over-incarceration of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Acrylic, pouring medium and beadwork through stretched canvas.

Unavailable

1 1/2 x 2 ft

“Kaashkikwaata - Mend”

2018

A visual depiction of the mediation process and its benefits within the practice of Family Law.

Acrylic paint, dispersion pigments, pouring medium and beadwork on stretched canvas.

Unavailable

1ft x 1 1/2 ft

“To Reconcile Wrongs”

2017

He hangs

A community other than his own

Gives birth to his death

Two worldviews exist in a single space

There is only room for one

The dominant one wins

Again

It is still winning.

- Kelly Duquette

Acrylic paint, gold leaf, pouring medium and beadwork through stretched canvas.

The noose: weaves through the painting from top right to bottom middle. Symbolizes Riel’s hanging, and the oppressive nature of pan-Indigenous approaches to inclusion.

The plantain: the plant in the top left corner is also called white-mans footprint. What I have been told is that it’s seeds were brought over on the clothing of settlers. It thrives in foreign environments. It also has medicinal properties. In this work, plantain represents the jury. With a similar history, this system can be changed to reconcile wrongs.

The six buds sprouting up and intertwined with the 6 figures together represent the 12 jurors.

The prairie smoke wild-flower: this whispy flower represents the Métis-the first flower to sprout after a prairie fire. After over one-hundred years of silence to avoid discrimination and persecution, there has been a revival of our Métis culture. Like the prairie smoke, we are resilient.

These flowers are weaved through the noose, representing the continuation of oppression, and suggest that our distinctiveness should be acknowledged.

The four sacred medicines: in the bottom right corner, these plants together represent possibilities of reconciliation through changes to the jury selection process.

During my summer employment, I became interested in Métis-specific participation in the jury selection process. This interest was born out of my failed attempts to put together public presentations on this topic. There was virtually no information out there on Métis and the jury selection process.

This past semester, I investigated this issue further in my directed research course called “Jury Selection and Representation”. Throughout this course I explored the flaws of our current jury selection process, and thought of ways it could be improved. While Indigenous people’s continue to be over-criminalized and over-represented in our prison system, they have been largely under-represented on juries... but the exact statistics remain unknown. My ultimate question came to be, “how can we assume that juries are performing their function as the conscience of the community, or that they achieve a standard of representativeness if we don’t value knowing the racial identity/ethnic background of those participating in the process, or care if an entire group is not engaged?”

I couldn’t help but reflect on the negative impact that Louis Riel’s trial, prosecution and death had on our people. In a place that was dominantly Métis, his jury consisted of all white protestants, a community other than his own. An oppressive death leading to further and continuous oppression within this system.

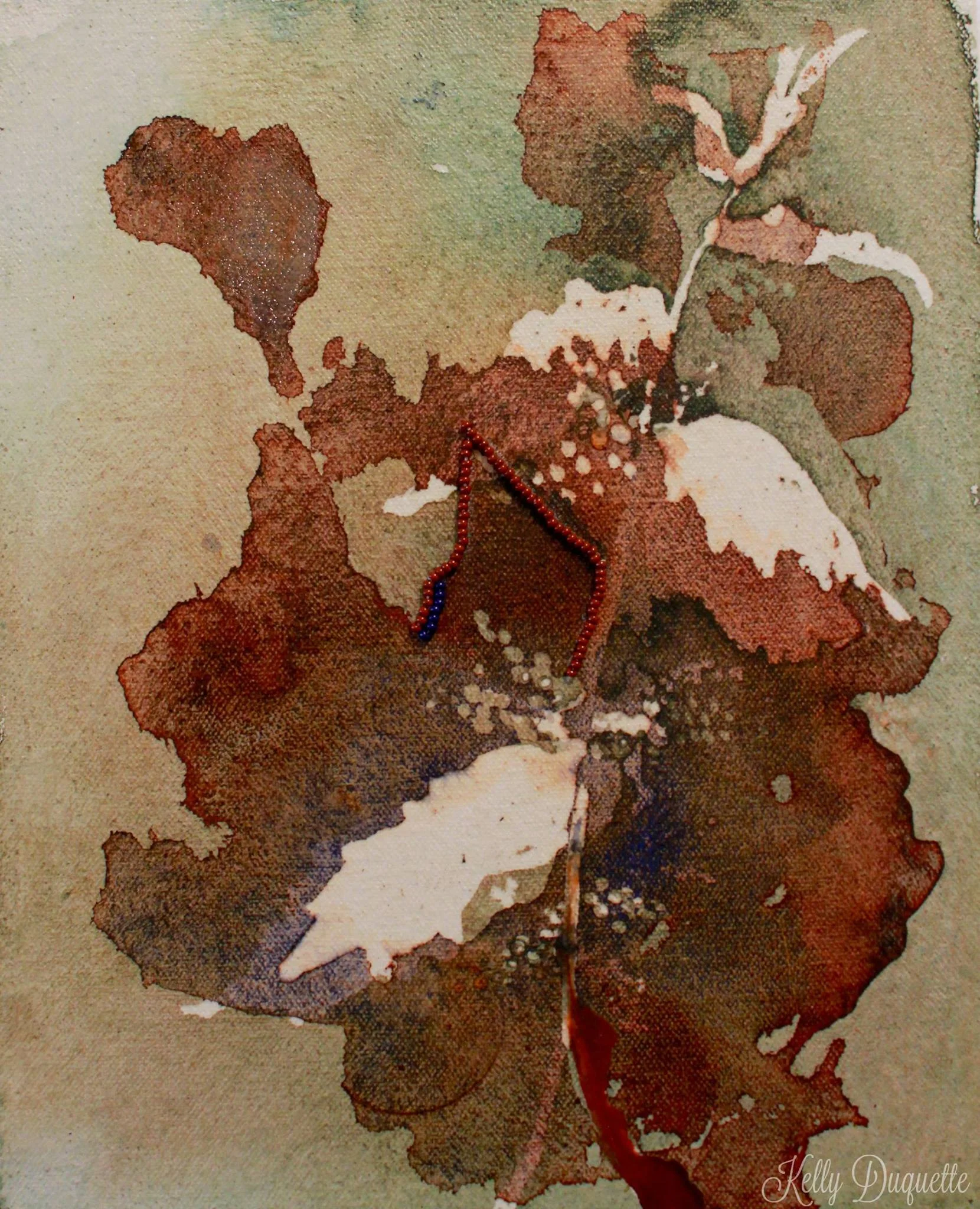

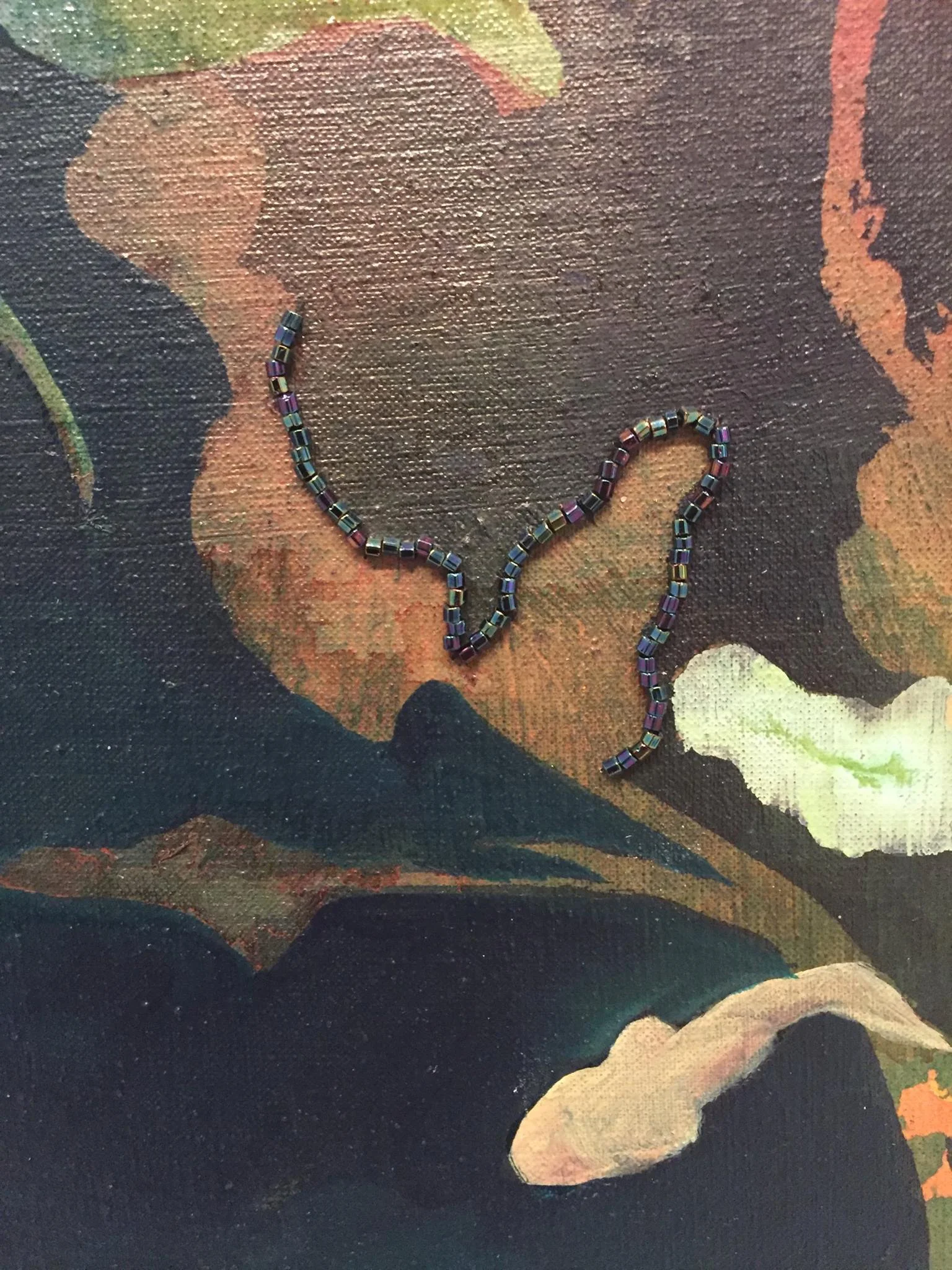

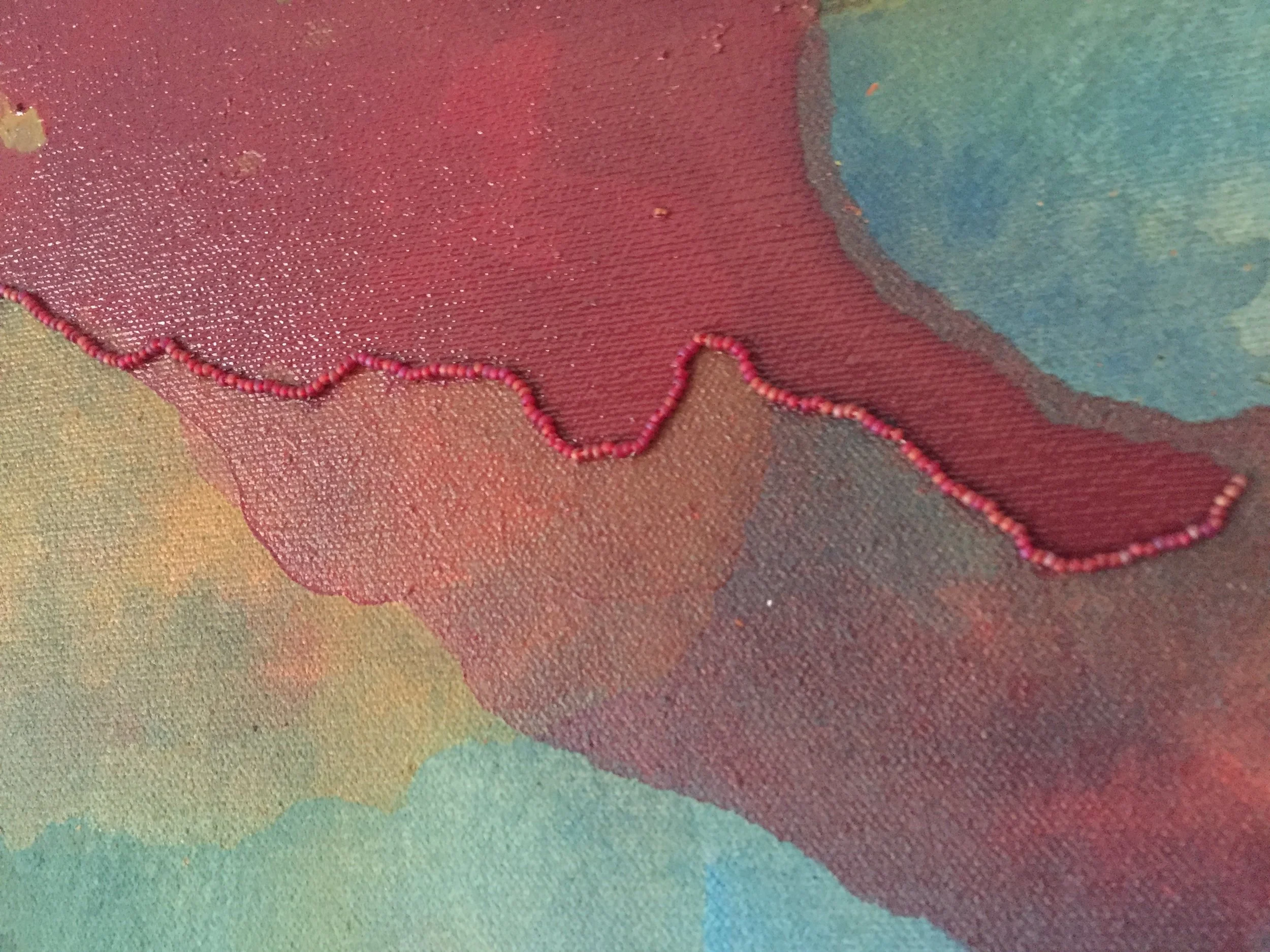

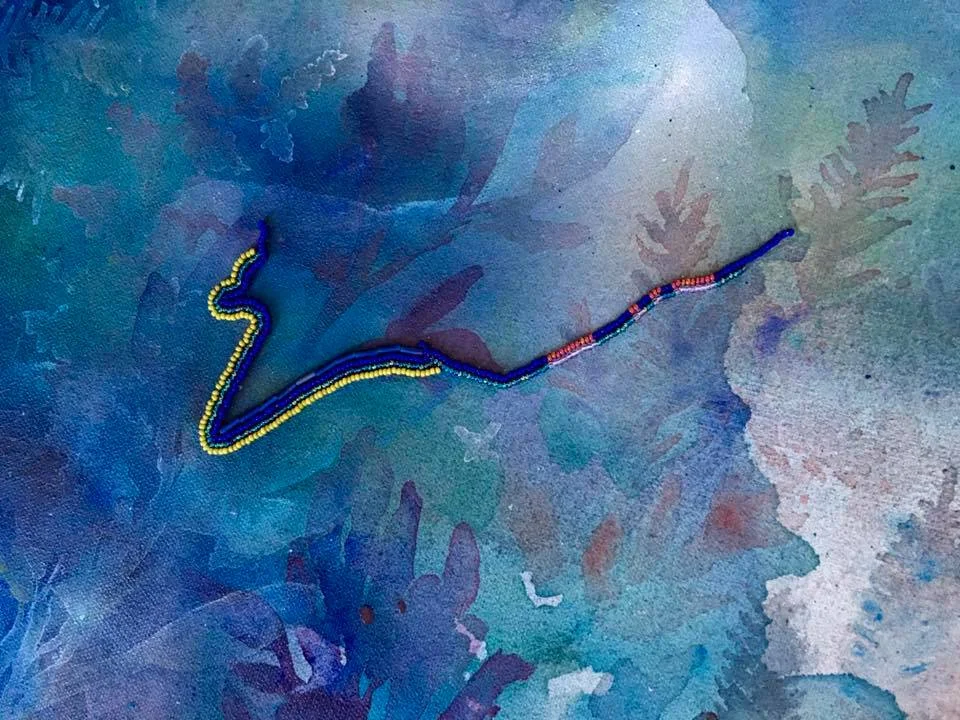

“Silent Knowledge”

2015

I have decided to name my series “silent knowledge”. After many years of silence and assimilation into the white-settler society, our people have forgotten our language, cultural practices and traditions. Since language is the main element of knowledge transfer, I feel that I have not been able to completely reclaim my Métis identity. I have chosen to reflect on this aspect of my life within this series.

For all ten pieces in the series, I have used Christi Belcourt’s book, Medicines to Help Us as my main point of research. Each painting is titled the Michif-Cree name of the plant in which it represents. When viewers of the series search for their titles of the paintings in the description cards they will realize that none of the medicinal uses are written in English, instead they are written in Michif-Cree. This process demonstrates the frustrations that I feel towards the loss of my language.

I have decided to construct the images of the plants out of negative space, further reinforcing the incomplete understanding that I have in regards to the significance of these medicinal plants, a barrier that presents itself in the form of language. The negative space also represents the disconnect that many urban Métis have with the land.

In each painting, I have incorporated minimal beadwork to demonstrate my attempts to reclaim my identity. It is one teaching that I hold onto. The Métis people are also referred to as the floral beadwork people. With our rounded glass beads, we have been able to create magnificent floral designs on our clothing and accessories. In the case of my paintings, I have not beaded flowers or plants, but rather, I have beaded on their images.

All of these incomplete elements in my work speak to the struggles of our people today, the time of re-birth, and the process of picking up where we left off many generations ago.

"Mazhaan"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Paviyoñ bleu"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Untitled"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Frrås"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Li tii'd mashkêk"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Eñ narbaazh di feu"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Plaañteñ"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"li sayd"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Sasparel"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

"Larbadeñ"

8" x 10"

Unavailable

“Maachipayin”

2016

2 x 2 1/2 ft

Unavailable

Acrylic paint, dispersion pigments, pouring medium and beadwork through stretched Belgian linen on hand-built stretcher.

-Was on display at the Gathering Place exhibition in the legislative assembly in Toronto from January 2017 - January 2018.

“Seven Sacred Teachings”

2016

"Seven Sacred Teachings" was displayed in the Gathering Place exhibition at the Toronto Legislative Assembly for the year of 2016. Each painting depicts the animal that embodies a given teaching.

Bear - Courage

Raven - Honesty

Wolf - Humility

Turtle - Truth

Buffalo - Respect

Eagle - Love

Beaver - Wisdom

"Courage"

12" x 12"

Unavailable

"Honesty"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

"Humility"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

"Truth"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

"Respect"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

"Love"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

"Wisdom"

10" x 12"

Unavailable

“I Forgot Who I was, But now I Remember”

2016

Acrylic paint, dispersion pigment, pouring medium and beadwork through Belgium linen on hand-built stretchers.

1/3

3 ft x 2 1/2 ft

$2000

2/3

3 ft x 2 1/2 ft

$2000

3/3

3 ft x 2 1/2 ft

$2000

Following over one-hundred years of silence, assimilation and oppression within Canadian society, the Métis peoples have begun to re-emerge and reclaim their culture. This unique time in our history has become an inspiration behind my artwork. Painting has allowed me to reflect on the issues related to my hidden identity and my experience as a Métis youth. The reductive quality of my work represents the loss of our language and traditions, while the intervention of abstract beadwork and acrylic paint reinforces our strength and resilience as a distinct rights-bearing people.

The series in Ode.

Edmund and Isobel Ryan Scholarship

This Scholarship is to reward a student graduating from the Bachelor of Fine Arts Program who demonstrates excellence in Painting.

The amount of the prize is $500. First Prize.

“Traveller”

2017

4 ft x 5 ft

Not Available

———OLDER WORK———

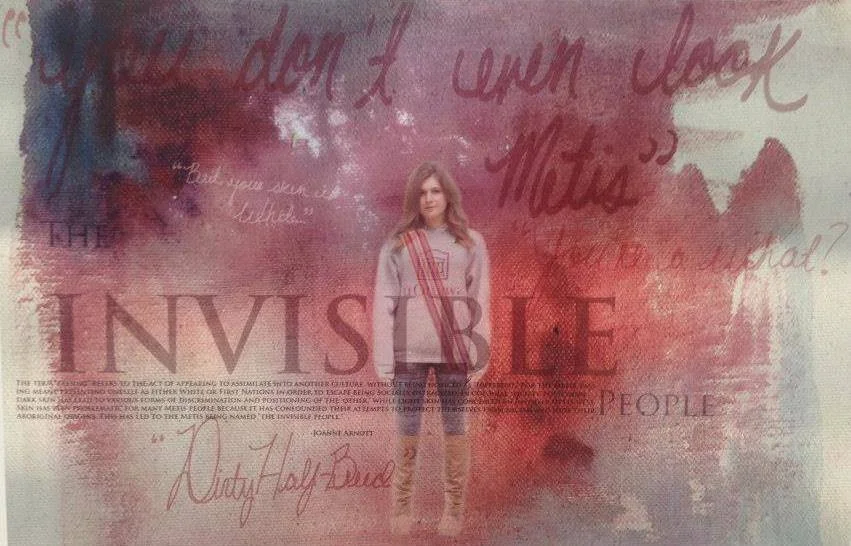

“You Don’t Even Look Métis”

2014

Acrylic on watercolour paper.

2 1/2 x 3 ft

"No offence, but you don't even look Métis"... A quote I hear so often by so many people. Métis identity is not racial, and it is not based in blood quantum or mixedness. The Métis(or “Michif”) nation emerged at a specific time in history in geographic areas outside of the control of the Canadian state. We as Métis embrace our historical and current ties to the Métis homeland, our shared culture and nationhood. Many people call us the invisible people, we blend into society, you cannot tell a Métis person by their appearance.

“Sash Series”

2014

I imagine this series of photographs to resemble old portraits of our ancestors. These are large format black and white film photographs. I shot them with a large format film camera, developed them in the dark room, scanned and inverted them, and painted all of the colour you see on photoshop.

Large format film camera (Not my photo)

This photo was given out to dignitaries at the 23rd MNO general assembly in 2016

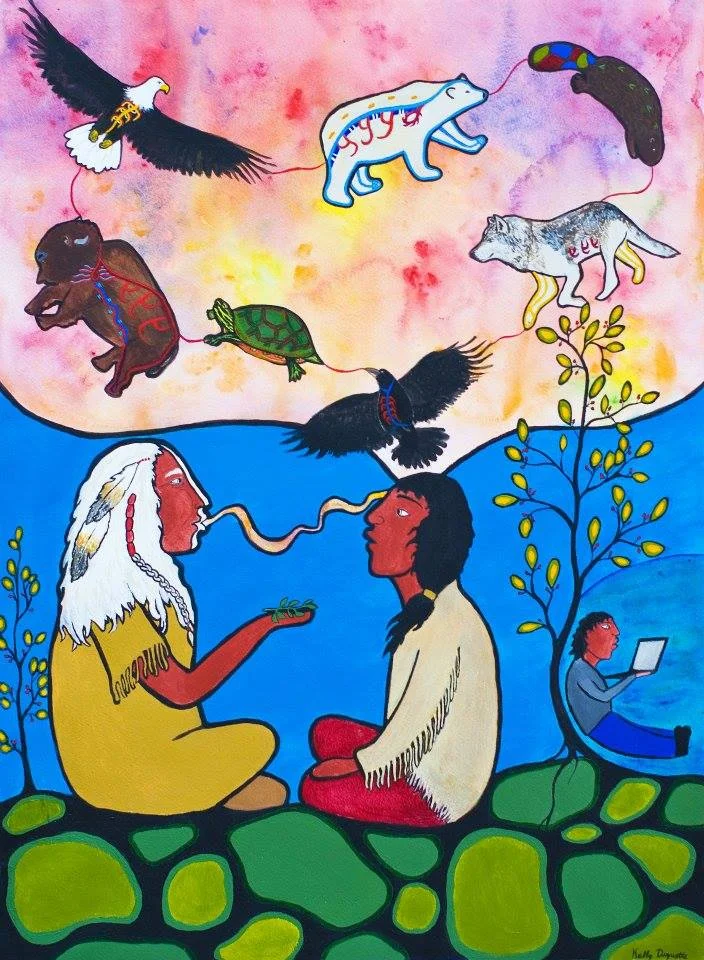

“Disconnected”

2011

Acrylic paint on stretched watercolour paper.

1 1/2 ft x 2 ft

Unavailable

“Disconnected” depicts an Elder passing teachings to a youth; each of the teachings is represented by its respective animal. However, the “disconnected” youth, lost in the world of his laptop, does not realize what is going on. It speaks about a gap in the transfer of Indigenous knowledge, and the realities Indigenous peoples face after years of colonization.

This was my first woodland style painting. I entered it into the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF) Student Achievement art competition and won an award. The theme of the year’s prose, poetry, visual arts, and audio/visual animation competition was, “The right to speak, the responsibility to listen”.

"Disconnected" can also be found on page 4 of David Bouchard's book, "Dreamcatcher and The Seven Deceivers".

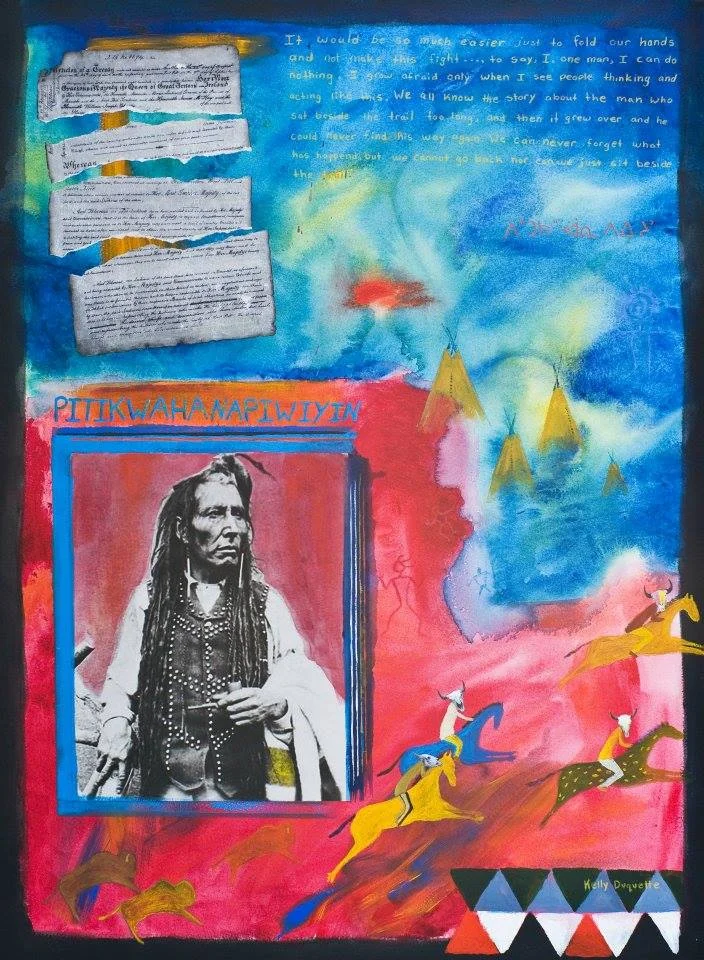

“Poundmaker”

2012

Acrylic washes, paper, photograph on stretched watercolour paper.

1 1/2 ft x 2 ft

Unavailable

I chose to do a mixed media piece of Poundmaker, therefore, what he stood for… a peacemaker. He exemplified the teaching of courage by standing up for what he believed was right despite the overwhelming government forces to create submissiveness.

The photo that I used of Poundmaker in the piece was very gallant, which even further illustrates his character and shows him as a proud, formidable being. I wanted to show this strength in my art. There were many aspects of life that had been lost. Aboriginal culture was ridiculed and shamed for many years. My family is just starting to learn about our rich, Metis heritage, which had been hidden away by our ancestors who were trying to fit into a European society.

There are still many issues and rights that we have to defend due to misunderstandings. I sometimes feel it in school and through our Metis council.

Recreating Poundmaker’s image helps up to remember and learn from our past, so that everyone will be encouraged to stand up for what is right and so others will respectfully listen. Then we will be heeding the message of our peacemaker…to walk in the path, instead of sitting beside it.

“Surmise”

2016

Can you spot the animals?

Acrylic washes and beadwork through stretched canvas and hand-built stretcher.

2 1/2 x 3 ft

$900

“The Monster Sturgeon”

2014

3D modelling paste, porcupine quills, beads, rocks, acrylic paint on stretched canas and hand-built stretcher.

2 1/2ft x 3ft

Unavailable

“Creation Story”

2014

3D modelling paste and acrylic painting on stretched canvas and hand-built stretcher.

1ft x 2ft

Unavailable

My visual interpretation of the turtle island creation story.

"Creation story" was featured as the month of July in the 2015 Donna Conna Calendar.

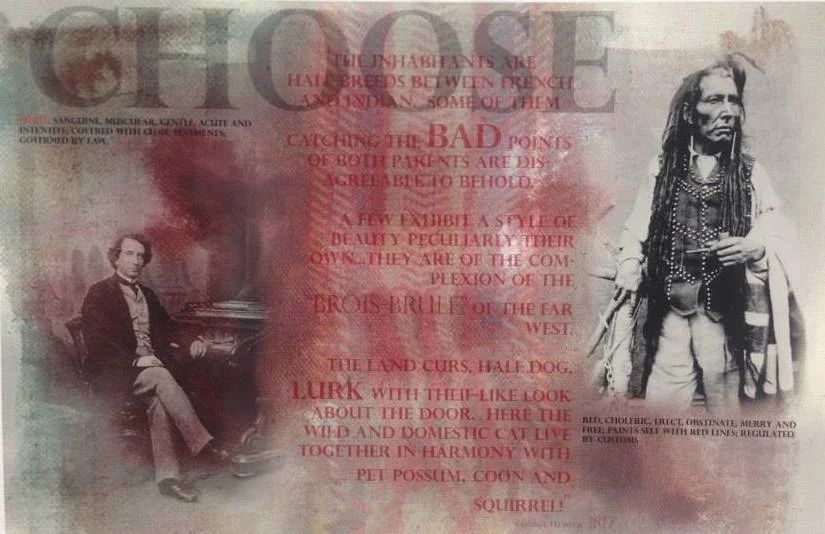

“Untitled Series”

2014

This digital photography series was inspired by Jane Ash and Carl Beams collage work. I used Photoshop to layer text, painting, historical images and my own photography and handwriting into one image. I spent time researching on our relationship with the government and our history fighting for the legal recognition of our rights.

"Choose"

Unavailable

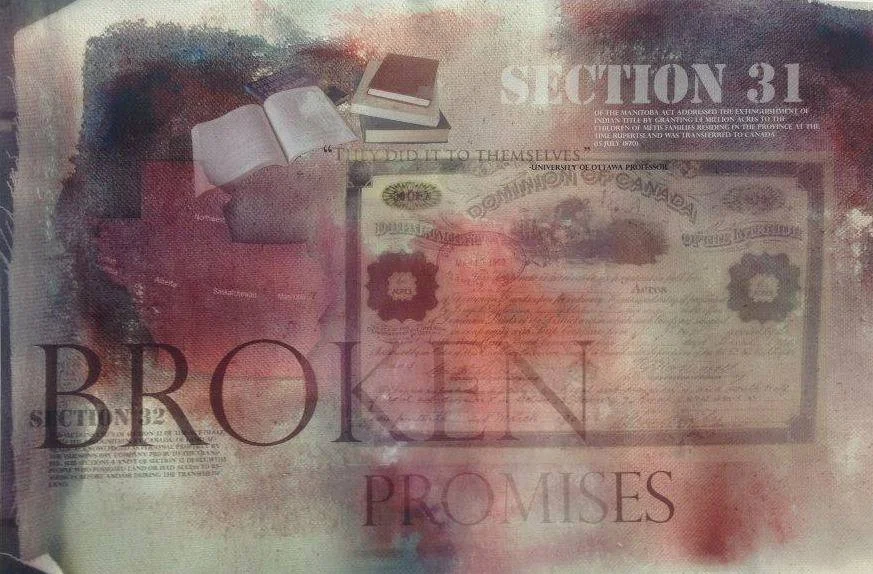

"Broken Promises"

Framed

17" x 22"

$100

"The Invisible People"

Unavailable

The piece titled, “Choose”, speaks about the scrip system and the government’s inability to understand or acknowledge our identity. We do not fit into a neat little box. All of our stories are different and it makes us hard to define. This has created many obstacles for us, and we have often been delegitimized for the abstract space we appear to float around in.

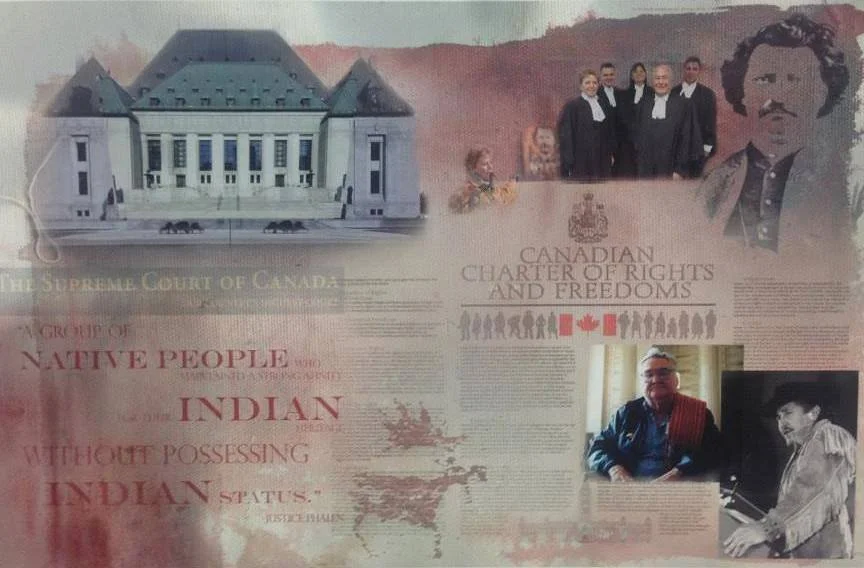

"The Fight for Legal Definitions"

Framed

17" x 22"

$100

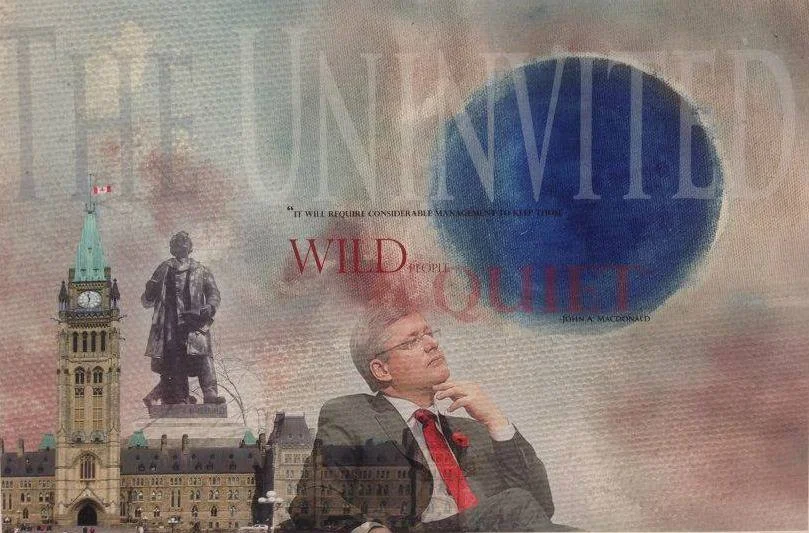

"The Uninvited People"

Framed

17" x 22"

$100